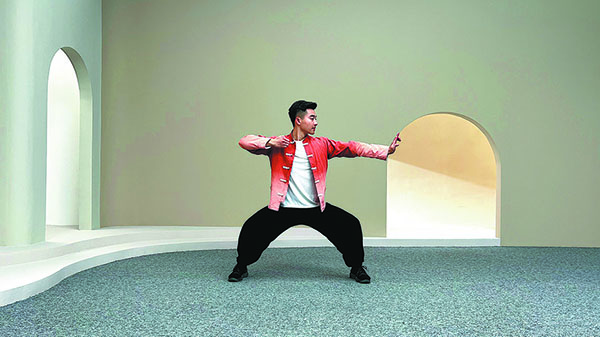

Once a sport for elderly, pandemic and government support give baduanjin younger profile, Chen Nan reports.

For 28-year-old model Huang Qian, going to the gym and following a strict diet help her maintain a slim figure.

About eight months ago, she decided to add a new form of exercise to her daily routine. Baduanjin — which translates as 'eight pieces of brocade — is a form of qigong, a set of traditional Chinese fitness exercises combining physical movement, with breathing and meditation.

"I knew nothing about baduanjin until I saw videos of people practicing on social media platforms. The movements are very slow, like tai chi, so I naturally associated it with the kind of exercise favored by the elderly," says Huang, who is from Hubei province.

Nevertheless, she decided to give baduanjin a try because she has issues with her cervical vertebrae, spleen and stomach.

"I read reviews, saying that it can be helpful to these kinds of problems," she says.

The practice doesn't require much space or time. Baduanjin uses breathing and concentration techniques to improve body and mind, through eight, well-designed sequences. Huang usually practices about half an hour after breakfast. She enjoys the exercise, which stretches and relaxes her whole body.

"I feel my body slowing down, as well as my mind. I concentrate on my movements while listening to beautiful, smoothing music. It only takes me 12 minus to finish the eight sequences. I feel refreshed and full of energy before starting my day," says Huang, who now practices baduanjin every day, in addition to going to the gym to do weight training and cardio.

When she found out that one of her favorite fitness influencers, German Pamela Reif, had added baduanjin to her workout videos, Huang was surprised and excited.

The video, which is 1 minute and 50 seconds long, has received more than 900,000 views, 49,000 likes and 24,000 reposts in the three weeks since it was posted on Bilibili, a popular video sharing platform, on Aug 8. It has helped introduce the ancient exercise to a wider audience, especially to young people like Huang. Film stars and fitness influencers who do baduanjin have also shared videos online, which has attracted many new practitioners.

"The popularity of baduanjin among young people is increasing, especially since people spent so much time at home during COVID-19," says 28-year-old Li Jianlin, who works as a fitness content creator for Keep, one of the most popular apps for sports lovers in China, and which offers online fitness programs.

"Many young people go to the gym, and workout regularly. However, a phased and slow approach to resuming exercise after COVID-19 is the best way to regain pre-COVID-19 fitness levels. So baduanjin, which is slow and smooth, has won the hearts of the young during recovery," says Li.

Li, who graduated from the Capital University of Physical Education And Sports with a major in aerobics in 2018, has created baduanjin exercise programs for the platform's users, which were launched earlier this year. Available in three different levels, the programs have received warm feedback from users.

"Seventy percent are young people, under the age of 30. The programs give detailed instructions and demonstrate the movements from different angles," says Li.

Keep's baduanjin programs have been watched more than 5.41 million times, and about 36,000 users have added them to their favorites.

"Since it also involves meditation and breathing exercises, it's also regarded as a way for young people to relax and cope with stress," he adds.

According to Wang Zhen, a professor at the Shanghai University of Sport, who teaches in its traditional Chinese sports program, baduanjin dates back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

Compared with other types of qigong exercise, such as tai chi and wuqinxi (in which practitioners imitate the movements of a bear, a tiger, a monkey, a deer and birds), baduanjin is more suited to beginners thanks to its simple, gentle movements.

"Each movement has its own set of rhyming instructions, which allows practitioners to easily memorize them, and move in time," says Wang.

"You can practice at almost any time and anywhere. For example, you can practice a standing posture by the table after sitting in front of the computer for a long time," Wang adds.

He started learning qigong when he was 12, introduced to the practice by his mother, who had high blood pressure, high cholesterol and hyperglycemia.

"She exercised at home so I followed her, just for fun," says Wang, who graduated from the Shanghai University of Sport in 1999 with a master's degree in traditional Chinese sports. He started to teach at the university later that year.

On June 5, 2001, the General Administration of Sport set up the Health Qigong Administrative Center, which provides scientific and professional guidance on qigong. In 2004, the Center published four books about four types of qigong, including baduanjin.

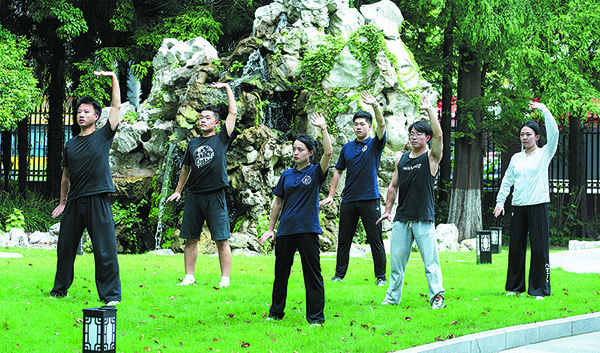

"Government support helped promote qigong exercises and baduanjin has developed a large fan base, not only among the elderly, but also among the young," says Wang.

In 2009, the university launched the Shanghai University of Sport National Science & Technology Park, which serves as an incubation center for sports enterprises, including traditional Chinese sports.

One of Wang's students is 23-year-old Liu Xueqing, who has been practicing baduanjin since 2019. Now pursuing her master's degree in traditional Chinese sports science at the Shanghai University of Sport, the 23-year-old also teaches seniors, young people and children in communities around Shanghai.

"I first learned baduanjin with my PE teacher when I was a freshman majoring in sports rehabilitation. At the beginning, it was boring because the movements are slow," says Liu. "But later, I found that it's very helpful for relaxing my muscles, especially after sitting for hours reading or writing."

"Now, baduanjin is a new fashion among the young," says Liu Xiaolei, associate professor of the martial arts school at the Beijing Sport University, who has posted baduanjin videos on social media platforms. One of them has been viewed over 200,000 times on Bilibili.

"In the past, only the elderly practiced baduanjin in parks or at home because it is not difficult. Now, I see many young people, either students or white-collar workers, practicing baduanjin," says Liu.

Liu served as president of the jury at the 11th Session of National Traditional Sports in Beijing, between Aug 21 and 25. Baduanjin was among the competitive games held at the event, which began in Beijing in 1985, and which includes a wide variety of traditional sports, such as martial arts, wresting and bahe (tug-of-war).

"We have people of all ages practicing baduanjin and like many traditions, such as hanfu (historic Chinese attire) and music, traditional sports is making a return to daily life," she says.

Related: